An old cowboy's thoughts about horses, canoes, fishing, art, movies, family, and the American West

Monday, May 30, 2016

Voyageur Legacy - LaPrairie Ancestors (1647 - 1699)

Land on the south side of the St. Lawrence was given to the Jesuits as a seigneury in 1647, only five years after the founding of Montreal. However, war with the Iroquois was raging and LaPrairie was an Iroquois settlement from which attacks were launched on Montreal. Consequently, it would not be until peace with the Iroquois was concluded following campaigns of the Carignan-Salieres Regiment that this seigneury could be settled. The Jesuits established a mission to the Indians in 1667 and opened the surrounding land for settlement. The majority of the first colonists came from Montreal, with a number from the Carignan-Salieres Regiment including Charles Diel (7ggf), Thomas Hebert, Antoine Rousseau, Jacques Testu, Mathieu Faye, and Jean Magnan. By 1670, the population of settlers was significant enough to open the seigneurial administration for LaPrairie de la Madeleine and also to establish the parish of St. Francois Xavier with the building of a chapel for the Indians and habitants on the seigneur’s estate bordering the river. Relations between the early settlers and the Indians were friendly, although many of the Indians soon left as the land was being settled.

This was an area of woods, prairies, lakes, rivers and stone quarries quite suitable for farming. By the end of 1673, the population of habitants in the seigneury was fifty-one men, thirty-six of them unmarried, fifteen women, of which six had come as girls from Montreal, and thirty-three children. But the population did not grow as fast as expected as the Jesuits were charging exorbitant rents, higher than those of the seigneuries run by French laymen, and the habitants were having trouble making payments. For the next two decades, the Jesuits tried to attract settlers by reducing the rents by half, but when the settlement was well established the rents were raised again. Several motives other than farming likely attracted the settlers. Initially the profits from the fur trade were all in the hands of the merchants but, after 1663, local traders started to emerge and included many soldiers who remained in New France after the wars with the Iroquois. The advantage of LaPrairie was that it offered a direct water route via the Richelieu River, Lake Champlain, and the Hudson River to Albany, the trading center for the English.

The dream of Pierre Perras (9ggf) and Denise Lemaitre (9ggm), among the early settlers, was to acquire a farm so that they could pass on to their growing sons an opportunity which would have eluded them in France. This was farmland easily accessible to the growing markets in Montreal. While it was hard work to prepare fields for cultivation, the Perrases had growing sons who could help. Pierre’s farm was a long, narrow strip of land extending back from his house near the St. Lawrence River, one in a line of houses in a settlement isolated enough that the habitants of Cote Saint-Lambert thought of their settlement as distinct from LaPrairie. The small house was built of timber, with a sloping roof and walls filled with clay. The main room had a few pieces of homemade rough furniture, a loom and, likely, a spinning wheel. The walls were bare except perhaps for a religious picture or two brought with them from France. The loft or attic was a busy sleeping place as the Perrases had nine living children.

The house and the nearby barn made of upright posts standing side by side with a straw thatched roof sat in a farmyard surrounded by post and rail fences. Wooden buckets used to carry water and a wooden washtub showed Pierre’s skills as a barrel maker. In the summer, sons and neighbors helped cut hay with a scythe and haul it to the barn on a cart drawn by oxen. At harvest time grain was bound into bundles and stored in the barn for several months until the men of the family flailed it on the threshing floor. Once the crops were harvested until planting time the next spring, aside from cutting firewood and doing the daily chores, there was time to jump in the sleigh and visit neighbors. Winter was a great social time, filled with drinking and smoking, playing cards, dancing and singing. The French habitants worked to the rhythm of work tunes as they threshed, cut wood, and did their chores, while the women did their spinning, weaving, and beating the wash to familiar tunes. The 1661 census showed Pierre Perras (9ggf) with ten acres under cultivation and six head of cattle.

The Perras family was devout Catholics. Attendance at church was difficult, however, because of the distance from either the seigneurial mansion or the Indian mission, with no road and the Saint-Jacques River to cross. Attendance was easier in the winter, when they could travel on the ice of the St. Lawrence. To host religious services at Saint-Lambert, Pierre and Denise donated a building on their farm 25 feet long and 20 feet wide with a thatched roof and dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The local habitants were responsible for maintenance. The Jesuits gave permission and agreed to offer Mass for the Saint-Lambert settlers. Pierre and Denise’ son-in-law, Pierre Poupart (8ggf), a local farmer, was one of the church wardens. In 1686, he sold a piece of land to Pierre Foubert and donated 218 livres for church furnishings. Because of the Iroquois threats, Jerome Lonctin, a local carpenter, dismantled the building at Saint-Lambert and built it back up inside Fort Saint-Lambert, recently built to protect the habitants. In 1686, the Jesuits turned the parish at LaPrairie over to the Sulpicians, who began plans to build a new parish church in LaPrairie. At the beginning of the 18th century, the building at Cote Saint-Lambert was torn down, and under the direction of Pierre Roy its furnishings were transported to the new church at LaPrairie.

Meanwhile, the number of families at Cote Saint-Lambert more than doubled and children were growing to adulthood. Denise must have been busy as a midwife for her own and others’ daughters. Four of the Perras daughters married men from Saint- Lambert between 1682 and 1690. In 1682, Marguerite Perras (8ggm), age 16, married Pierre Poupart (8ggf), who had come to Quebec as a domestic for Pierre Gagnon and later bought a farm at Saint-Lambert. Pierre and Marguerite had seven children before Pierre was killed by the Iroquois at age 40 in 1699 and Marie married a second time to Joseph Boyer. At age 18 in 1688, Catherine (9gga) married Eustache Demers, son of local neighbors Etienne Demers and Jeanne Denote, and this couple had 10 children. Later that year, Jeanne (9gga), age 17, married Claude Faye, who had come from France and bought land at Saint-Lambert in 1682. Jeanne and Claude had eight children, while Claude worked in the fur trade. After Claude’s death, Jeanne married Pierre Jolibois. In1690, Marie, age 17, married Antoine Jacques Boyer, son of Saint-Lambert pioneers Charles Boyer (9ggf) and Marguerite Tenard (9ggm). Marie and Antoine’s oldest child of seven, Marie Boyer, later married Jean Francois Patenaude.

Pierre Perras (9ggf) died on April 30, 1684 at LaPrairie. Because of Pierre and Denise’ hard work, at the time of his death they had two farms, one barn, one stable, eleven cattle and six pigs. Yet the revenue from the farm was not enough to support Denise with her large family so she got involved in fur trading with the Catholic Iroquois to make ends meet. Probably resulting from her involvement in the fur trade, a Montreal merchant, Francois Pougnet, had a lawsuit going against Denise in 1687 over a business deal. Denise appealed the sentence in Montreal in 1687, again at Trois Rivieres later that year, and the case was finally brought to the Sovereign Council in January, 1688. In October of 1684, Denise Perras (9ggm) married Francois Cael, another pioneer, at LaPrairie. Denise had at least four children left at home and Francois brought eight minor children into the marriage. When Francois Cael died in 1687, Denise sold their land to her son-in-law, Eustache Demers. Denise still had a family to support and went back to the skill she had learned in Paris, practicing midwifery until her death.

During this time, the attacks by the Iroquois were escalating and a number of habitants from Saint-Lambert sought shelter in the fortification at Montreal. Denise (9ggm) remained behind and was killed at age 55 by the Iroquois at Cote-Saint-Lambert on October 29, 1691, when a group of Dutch and Indian fighters led by Major Peter Schuyler of New England struck the French in reprisal for the French attack on Schenectady. Denise’ daughters were by this time busy raising big families while her sons were still unmarried and likely away in the fur trade. Ironically, Denise’ granddaughter Marguerite, the daughter of Pierre Poupart (8ggf) and Marguerite Perras (8ggm), was also killed by the Iroquois as an eleven year old at LaPrairie in 1696.

Pierre (9ggf) and Denise (9ggm) had only a few grandchildren to pass on the Perras name. Their oldest son, Pierre, died at age 27 in 1687. Their second child, Jacques, died at age 25 in 1688. The Perras sons were more interested in the fur trade than in farming. Jacques received a concession of land in 1679 and sold it in less than one year to A. Marsil. Jean Perras, also in the fur trade, married twice; the first time with Marguerite Testu, with whom he had one child, and secondly with Madeleine Roy, the daughter of neighbors Pierre Roy and Catherine Ducharme. Jean and Madeleine had eight children, including their son, Andre, who married Marie Catherine Leber, the daughter of Francois Leber (8ggu) and Marie Ann Magnan. The youngest son of Pierre Perras (ggf) and Denise Lemaitre (9ggm), born after they moved to Cote Saint-Lambert, also used the name Pierre. Pierre and his brother-in- law, Antoine Boyer (8ggf), bought land conjointly in 1690 for 600 livres from the sale of beaver pelts. Like his brothers, he was away in the fur trade, marrying only at age 36 to Marguerite Diel. He died three years later, leaving his widow with a fifteen month old son.

Like the Perras family, members of the Patenaude family had relocated from Ile d’Orleans to work in the fur trade. Charles LeMoyne in the neighboring seigneury of Longueuil gave concessions to Pierre and Charles Patenaude. Pierre married Catherine Brunet and they parented ten children. The oldest brother, Jean Patenaude, first married Marie Brunet, sister of Catherine, with whom he had two children, and had a second marriage to Marie Robidou, daughter of Andre Robidoux (9ggf) and Jeanne Denote(9ggm) of Cote Saint-Lambert. Jean and Marie’s son, Jean Francois Patenaude, married Marie Boyer, the daughter of Antoine Boyer (8ggf) and Marie Perras (8ggm). Charles married Francoise Seguin, daughter of Francois Seguin and Marie Petit, and they parented ten children. Elizabeth, the younger sister of the Patenaude men, married Jean Ferron, a soldier, shoemaker, and fur trader, and they raised their nine children in Montreal.

Among these early settlers in the LaPrairie seigneury, we can recognize many familiar names of our ancestors. Charles Boyer (9ggf) and Marguerite Tenard (9ggm) earned their farm by serving as domestic servants to the Jesuits. Housed by the Jesuits, their responsibilities included delivering 500 pounds of wheat to Montreal annually, preparing food for the priests and guests, providing 12 pounds of bread weekly, cutting 12 cords of stove wood, and maintaining the fences and bridges. They received a farm with two arpents along the river when they finished their commitment. Even during the time that he served as a domestic servant, Charles Boyer (9ggf) was also involved as a coureurs des bois in the fur trade. It was their son, Antoine (8ggf), born at LaPrairie in 1671 and a captain in the local militia, who married Marie Perras (8ggm).

Denis Brosseau was the miller at a mill the Jesuits built to grind the habitants’ wheat. The farmers were obligated to grind their grain at the mill, which was built as a service to the community. Denis signed a five year contract as miller in 1692. Denis and his wife, Marie Madeleine Hebert, had eight children and, since he could not make enough at the mill to support his family, he bought two farms totaling 100 arpents for 600 livres, which he would pay off in annual installments. They had their home in the village. Their son, Pierre, also a miller, was married to Barbe Bourbon, daughter of Jean

Bourbon, who was killed in the battle at LaPrairie in 1690 when Dutch forces and Indians led by Peter Schuyler of Albany were retaliating for a raid led by Pierre LeMoyne. Governor Frontenac had gathered 1200 military and habitants at LaPrairie to counter this attack. It was Schuyler’s forces that would be responsible for the death of Denise Lemaitre (9ggm) the next year.

Jean Bourbon’s wife, Anne Marie Benoit, was the daughter of Paul Benoit and Elizabeth Gobinet. They had four daughters before Paul was killed. In 1695, Jean Besset decided to defy his father’s authority and marry Anne Marie Benoit. His father, a former Carignan-Salieres soldier now farming, judged this a poor union and was scandalized that his twenty-three year old son would marry an older widow with three children and tried to stop the wedding. The vociferous elder Besset appeared with witnesses and threatened the priest if he married the couple, but the priest deemed the consent of the

marrying parties was mutual and authentic and witnessed the marriage of the couple at the 6:00 a.m. Mass at Ville Marie on May 16, 1695. Jean and Anne Marie had one daughter, who was buried on May 25, 1697. In August of that same year, the Iroquois struck again and tried to take Anne Marie captive. She defended herself valiantly, but, like her first husband, died of her wounds. Ironically, her second husband, Jean Basset, along with Eustache Demers, had been captured by the Iroquois in 1693. Both were scalped and left for dead but survived to tell about it.

Charles Deneau (8ggu), the son of a pioneer of Montreal, was married to Madeleine Clement at LaPrairie. Charles and Madeleine had eleven children. Charles was one of the first coureurs des bois with the Ottawa Indians and did not return from one of his trips. Their son, Charles, married to Marie Anne Demers, was the father of Genevieve Deneau, who with her husband, Pierre Pinsonneau, were the grandparents of Joseph Perras. As was the case with so many intermarriages between families in the community, Charles and Madeleine’s son, Claude, married Marie Poupart (8gga), the daughter of Pierre Poupart (8ggf) and Marguerite Perras (8ggm).

Two Demers brothers, Joseph and Eustache, were pioneers at LaPrairie. Joseph, who had been a domestic for the Jesuit mission among the Outaouis, married Marguerite Guitaut and was a major in the militia at LaPrairie. Their son, Jacques, married Marie Barbe Brosseau, the miller’s daughter. Jacques and Marie Barbe’s daughter, Marie Anne Demers, married the second generation Charles Deneau (8ggu). Joseph Demers was also the second husband of Marguerite Perras (8ggm), the widow of Pierre Poupart. Eustache Demers was the husband of Catherine Perras.

Andre Robidou (9ggf) was a Spaniard who came to New France in 1661 as an engage of Eustache Lambert, a prominent interpreter, settler and fur trader. Andre was a sailor living with his employer. In 1664, Andre received a concession of land on Ile d’Orleans and another in 1665 at Cote Lauzon near Quebec. His wife, Jeanne Denote (9ggm), came to Quebec in 1666 and resided at a house on the grounds of the Ursuline monastery until she married Andre on June 17, 1667. In 1771, Andre and Jeanne moved to the village of LaPrairie with their first daughter, Marie Romaine, most likely because of involvement in the fur trade. In 1672, Andre acquired property on the Cote de la Riviere Saint-Jacques near LaPrairie, which he exchanged in a few months for property at Cote de la Tortue of LaPrairie. He also sold his property in the village. Andre and Jeanne had four more children before he died in 1679, when their youngest child, Joseph, was three months old. Four months later, Jeanne Denote married Jacques Suprenant, a soldier originally with the Carignan Salieres Regiment, with whom she had eight more children at LaPrairie. Son Joseph Robidou married Jeanne Seguin, and they were the grandparents of Etienne Perras. Joseph would later be well known in the fur trade at Detroit. Daughter Marie Robidoux married Jean Patenaude and they became the parents of Jean Francois Patenaude.

Trouble with the Iroquois started up again with vigor in 1684. Because of Iroquois threats, Governor LeBarre designated LaPrairie as a frontier against the English and Iroquois and a fort was built around LaPrairie in 1687. The fortification would surround the habitants and animals for refuge in case of an attack. Another fortification was constructed at St. Lambert.

LaPrairie was a major target of the two reprisals by the Iroquois for the French attacks on Albany. On August 30, 1690, responding to four cannon shots which served as a signal to reassemble, troops who were now dispersed to help with the wheat harvest hurried back to the fort. 1200 men gathered at LaPrairie. Governor Frontenac of Montreal was alerted to the presence of Iroquois near Lake Champlain but, when scouts did not find any traces of the Indians, they returned to their quarters. On September 4 th, the Iroquois stealthily attacked the habitants and soldiers harvesting wheat. Unfortunately, the French had failed to post sentinels or to have a guard ready to resist. The consequence was that eleven habitants, three women, one girl, and ten soldiers were killed or captured. Before help could arrive, the Iroquois had set homes and haystacks on fire and slaughtered the farm animals. Among the habitants killed in this attack was Jean Bourbon.

On August 11, 1691, Major Peter Schuyler led another surprise attack on a much larger force of 800 French and allies at the fort at LaPrairie. Schuyler’s force attacked in a rainstorm just before dawn, inflicting severe casualties before withdrawing to the Richelieu River. This was the raid in which Denise Lemaitre (9ggm) was captured and lost her life. Schuyler’s force was intercepted by a force of 160 men who were detached to block his road to Chambly. Among the habitants who participated in this expedition to revenge these attacks we find the names of Jacques Perras, Pierre Poupard (8ggf) and Francois Cael. The two sides fought in vicious hand-to-hand combat for about an hour before Schuyler’s force broke through and retreated back to Albany. As mentioned, some of the families sought refuge at Montreal because of the dangers. On the positive side, a few of the Troops de la Marine decided to settle at LaPrairie, including Claude Guerin. When the fighting was ended, Claude received a plot of land in payment for his services. His neighbors introduced him to a widow whose property included the prime source of water in the area, a natural spring. The widow, Marie Cusson (8ggm), the daughter of habitants Jean Cusson (9ggf) and Marie Foubert (9ggm), was one of sixteen children and had already been widowed twice. She had settled at LaPrairie with her first husband, Jean Bareau, and they had five children when Jean was killed by the Iroquois. Two years later she married Joachim Leber, who was lost on a fur trading expedition to the west, with whom she had a daughter. She was thirty-three when she married Claude Guerin and they added four more children to the family before Marie was left again as a widow with small children.

LaPrairie grew between 1694 and 1697 as Iroquois hostilities diminished. A number of new residents sought refuge there, including merchants, craftsmen and skilled workers. By 1697, the fortification enclosed 120 persons, among them Charles and Jacques Deneau (7ggf), Francois Leber (8ggf), Denis Brosseau, Francois Bourassa (7ggf) and Claude Guerin.

The story of the Bourassa family is somewhat typical of the times. A native of France, Francois Bourassa (7ggf) married Marie Leber (7ggm), the daughter of LaPrairie pioneers Francois Leber (8ggf) and Jeanne Testard (8ggm), and widow of Charles Robert. After five years of marriage, Francois was captured during a skirmish with the Iroquois and presumed dead but returned after a prolonged absence. Francis and Marie had seven children, with five living to adulthood. Their daughter, Marie Leber (6ggm), married Jacques Pinsonneau (6ggf). Francois Bourassa had two concessions of land and also a home in the village of LaPrairie but had prospered even more by being involved as a fur trader in the west. When Francois died at age 48 in an epidemic at Montreal, Marie married a third time to Pierre Herve. Like most of the families of LaPrairie at this time, the Bourassa family watched their sons head west to make a profit in the fur trade.

Lineage and Pedigree:

Denise Lemaitre (1635-1691) - my 9th great-grandmother

Marguerite Perras dit La Fontaine (1665-1708) - daughter of Denise Lemaitre

Joseph Poupart (1696-1726) - son of Marguerite Perras dit La Fontaine

Marie Josephe Poupart (1725-1799) - daughter of Joseph Poupart

Pierre Barette dit Courville (1748-1794) - son of Marie Josephe Poupart

Marie Angelique Baret dite Courville (1779-1815) - daughter of Pierre Barette dit Courville

Marie Emélie Meunier dit Lagassé (1808-1883) - daughter of Marie Angelique Baret dite Courville

Lucy Passino (1836-1917) - daughter of Marie Emélie Meunier dit Lagassé - 2nd great grandmother

NOTE: Great Grand-Father = (_ggf); Great Grand-Mother = (_ggm), etc

Source "Minnesota, eh?" pages 68 -- Chapter 6 LAPRAIRIE: Second Generation Perrases, Patenaudes, et al.

Sunday, May 29, 2016

Great Grandma was an Orphan, Killed by Indians

The fascinating story of my 9th great grandparents Pierre Perras and Denise Lemaitre

Pierre Peras or Perras, dit(1) Lafontaine, was the first Perras to come to Québec. He was the son of Pierre Peras, a baker in St-Jean-du-Perrot, a parish in La Rochelle and of Jeanne L'Asnier.

He was born in La Rochelle, Anis, France and was baptized on the 21st of August 1616 in the Sainte Marguerite chapel. He had two sisters: Marie and Catherine.

We know that in Québec he was a 'tonellier': a master tradesman skilled in the art of making of wood barrels. It is also known that he signed a marriage contract on the 10th of January 1660 with Denise Lemaistre. The marriage took place on the 26th of January 1660 in Ville Marie (Montréal) in the presence of Jeanne Mance, Jacques Lemoyne and Louis Charier, a surgeon.

They had ten children together. Pierre Peras died on the 30th of April 1684 in Laprairie, Québec.

Denise Lemaistre, his spouse, was better known and, therefore, more is known about her life. She was born in Paris in 1636 the daughter of Denys-David Lemaistre and of Catherine Deharme. They lived on rue St-Antoine and worshiped in the St-Paul parish church.

Her mother died while Denise was still a young girl. She was consequently put in pension in the "Hôpital de La Pitié" of Paris. Since, in those days, the king (or his administration) paid for almost everything, the hospital was also known as the "Hôpital du Roi", the King's Hospital and any orphan child leaving the hospital at maturity was known as a "Fille du Roi" or "Fils du Roi" - the King's daughter or the King's son.

While at the hospital, Denise obtained the certificate of Midwife. Jeanne Mance, who was looking for girls of good morals, with constitution capable of enduring many hardships and possessing an education that would be useful in the new world, naturally came to the hospital to find them. So it was, then, that Denise Lemaistre became part of the first group of "Filles du Roi" which came to Québec.

Denise set out on her voyage on a ship called the St-André whose captain was named Poulet. The ship sailed from La Rochelle on the 2nd of July 1659. There were 109 persons aboard, some of whom would serve pivotal roles in the early history of the new colony of Nouvelle France.

On the 7th of September 1659, the vessel laid anchor at the foot of the Cap Diamant, Québec. From the onset of the voyage, the plague had reared its ugly head aboard the non-disinfected vessel. The food, which was mediocre at best, had been rationed. Fresh water was also rare so that the hard biscuits served to the passengers had to be crushed with cannon balls to make them edible.

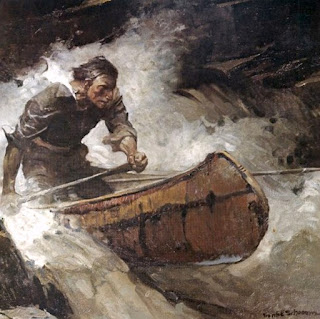

One can imagine the tireless efforts put forth, upon arrival in Québec, by Denise Lemaistre, Jeanne Mance, Marguerite Bourgois and the other Filles du Roi to help the sick and the dying. After three weeks of helping the sick, Denise slowly found her down to Ville-Marie using the only safe mode of transportation, a canoe.

Once she arrived in Montréal, she went into service with the Hospitalières de St-Joseph. Hardly one week passed by before a Montréal pioneer solicited her hand in marriage.

So on the 5th of October, Denise Lemaistre and André Heutibise signed a marriage contract. However, on the 2nd of December 1659, he died in the arms of his fiancée, mortally wounded in a battle with the Iroquois.

The hard life in the new colony in those days did not allow individuals to grief for very long. Therefore, barely a month later, on the 10th of January 1660, and in front of the same notary, Sevigne Basset, she signed a new marriage contract with Pierre Pera dit Lafontaine, tonellier from St-Jean-du-Perrot in the La Rochelle diocese. The marriage took place on the 26th of January as mentioned above.

Note that he signed his name in small letters. At that time, capital letters were optional: pierre pera. His family got that name from Pérat, a small community of Salignac-en-Pons, 25 kilometers from Xaintes, a village in Charente-Inférieure. His trade did not provide enough of an income to buy the necessities for his family. So, on the 25th of August 1667, Pierre Pera bought a 24-acre farm on the edge of the St-Pierre valley between the farms of Pierre Malet and Jacques Beauchamp.

Denise and Pierre had ten children. At the 1681 census, it was noted that they had a 40-acre farm with ten of those acres under cultivation and six heads of cattle. It was further noted that their two oldest sons were absent: they were in the fur trading in the deep forest. Six of their children got married, three of them twice. We are descended from a daughter, Marguerite Perras dit Fontaine, who was born on December 27, 1665, in Montréal, Quebec. Only two of the sons, Jean and Pierre, carried out the Perras name. Pierre Pera never had a chance to see all his children grow up, get married and settle down.

He died the 30th of April 1684. Because of their efforts and hard work, they possessed, at the time of his death, two farms, one barn, one stable, eleven heads of cattle and six pigs.

But even the revenue from all those assets was not enough to support her large family so Denise had to do some fur trading with the Catholic Iroquois to make ends meet.

Eventually, on the 9th of October 1684, she married François Cahel, another pioneer. Three years passed before another catastrophe came into her life: her second husband died on the 18th of November 1687.

Denise Lemaistre did not contemplate starting a family for the third time. Instead, she went back to the skill she had learned in Paris. She practiced midwifery until her death. She died as a martyr for the colony. On October 29th 1691, in the village of Côte St-Lambert, she was killed and massacred by the Iroquois. She was 55 years old.

source (edited): https://familysearch.org/photos/stories/4211946

(1) The term 'dit' means surnamed. It was used extensively in 17th century France as a way to tack on another name to the given names of a person. It was a mean of distinguishing between similarly named individuals. Not much is known about his trip to Québec.

Our Lineage form Pierre Perras, dit Lafontaine:

Pierre Peras dit La Fontaine (1616 - 1684) - my 9th great-grandfather

Marguerite Perras dit Fontaine (1665 - 1708) - daughter of Pierre Peras dit La Fontaine

Joseph Poupart (1696 - 1726) - son of Marguerite Perras dit Fontaine

Marie Josephe Poupart (1725 - 1799) - daughter of Joseph Poupart

Pierre Barette dit Courville (1748 - 1794) - son of Marie Josephe Poupart

Marie Angelique Baret dite Courville (1779 - 1815) - daughter of Pierre Barette dit Courville

Marie Emélie (Mary) Meunier dit Lagassé (1808 - 1883) - daughter of Marie Angelique Baret dite Courville

Lucy Passino (1836 - 1917) - daughter of Marie Emélie (Mary) Meunier dit Lagassé

Abraham Lincoln Brown (1864 - 1948) - son of Lucy Passino

Lydia Corinna Brown (1891 - 1971) - daughter of Abraham Lincoln Brown - my grandmother

Saturday, May 28, 2016

Great Granddad was a member of the Traite de Tadoussac

Denis Duquet - my 8th great-grandfather - was born 1605, in La Rochelle, Aunis, France; he died November 26, 1675 in Lévis, Québec, Canada.

Denys (Denis) was born in Normandie France about 1605. He was the son of Joseph Duquette and Jeanne Barbie. His surname was written as Duquay on his marriage certificate in 1638.

He had immigrated from France to Canada around the year 1633.

He married Catherine Gauthier (Gautier) 13 May 1638 in Notre Dame, Quebec (Nobelman Pierre Legardeur and M. Noel Jucherau were witnesses). Catherine was just 13 at the time of her marriage, but they had been married for 37 years, at the time of his death in 1675. Catherine Gautier was born Abt. 1627 in Paris, France; she died 03 August 1702 in Canada. She was the daughter of Phillipe Gautier (Gauthier) and Marie Pichon (Plichon).

1659: As a young man Denis Duquet became a wealthy fur trader. He became a member of the "Traite de Tadoussac" (1) the first fur-trading post in European North America (established in 1600, eight years before the founding of Québec City). The Traite de Tadoussac was the embarkation warehouse and trading post from which the furs were sent to France.

Denis was noted in the records to be the brother in law or beau-frere, of two presidents of the Societe des Habitants.

1660: Denis was named an Honorable Gentleman.

1667 census for Cote de Lauzon: Denis 55, Catherine 42, Pierre la Chesnais, notary, 25, Francoise 23, Agnes 19, Jean Desrochers 16, Rosalie 14, Louis 10, Philippe 8, Antoine 6, Catherine 5, Joseph 3. Domestic Servants: Simon Duval (no age given) and Claude 17. Property: 8 beasts and 30 arpents cultivated land.

27 November 1675: From the Parish of Notre-Dame Quebec: 27 November 1675, Denis Duquet, a resident of the coast of Lauzon, died at the age of seventy years. He was living in the hospital of Quebec, and died after having received the Holy Sacraments of Last Communion and Extreme Unction.

Denis Duquet and Catherine Gauthier had 11 children: i. Pierre Duquet 1643-1687, ii. Francoise Duquet 1645-1719, iii. Agnes Duquet 1648-1702, iv. +Jean Duquet dit Derochers 1651-1710/18, married Catherine-Ursule Amiot, v. Rosalie Duquet 1654-1715, vi. Louis Duquet 1657-1691, vii. Philippe Duquet 1659-1683, viii. Antoine Duquet 1660-1733, ix. Catherine Duquet 1662-1681, x. Joseph Duquet 1664-1731, xi. Marie Therese Duquet 1667-1699

|

| Tadoussac, lying at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers |

(1) Tadoussac was founded in 1600 by François Gravé Du Pont, a merchant, and Pierre de Chauvin de Tonnetuit, a captain of the French Royal Navy, when they acquired a fur trade monopoly from King Henry IV. Gravé and Chauvin built the settlement on the shore at the mouth of the Saguenay River, at its confluence with the St. Lawrence, to profit from its location. But the frontier was harsh and only five of the 16 men with them survived the first winter. In 1603, the tabagie or "feast" of Tadoussac reunited Gravé with Samuel de Champlain and with the Montagnais, the Algonquins, and the Etchimins."

Tadoussac (French pronunciation [tadusak]) is a village in Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers. Established at an Innu settlement, it was France's first trading post on the mainland of New France. By the 17th century it became an important trading post and was the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in Canada, and the oldest surviving French settlement in the Americas.

The indigenous Innu called the place Totouskak (plural for totouswk or totochak) meaning "bosom", probably in reference to the two round and sandy hills located on the west side of the village. According to other interpretations, it could also mean "place of lobsters", or "place where the ice is broken" (from the Innu shashuko).

Although located in Innu territory, the post was also frequented by the Mi'kmaq people in the second half of the 16th century, who called it Gtatosag ("among the rocks"). Alternate spellings of Tadoussac over the centuries included Tadousac (17th and 18th centuries), Tadoussak, and Thadoyzeau (1550)

My Lineage from Denis Duquet:

Denis Duquet (1622 - 1675) - my 8th great-grandfather

Jean Duquet dit Desrochers (1651 - 1710) - son of Denis Duquet

Etienne Duquet dit Desrochers (1694 - 1754) - son of Jean Duquet dit Desrochers

Marie Madeleine Duquet (1734 - 1791) - daughter of Etienne Duquet dit Desrochers

Gabriel Pinsonneau (Pinsono) (1770 - 1813) - son of Marie Madeleine Duquet

Gabriel (Gilbert) Passino (Passinault) (Pinsonneau) (1803 - 1877) - son of Gabriel Pinsonneau (Pinsono)

Lucy Passino (1836 - 1917) - daughter of Gabriel (Gilbert) Passino (Passinault) (Pinsonneau)

Abraham Lincoln Brown (1864 - 1948) - son of Lucy Passino

Lydia Corinna Brown (1891 - 1971) - daughter of Abraham Lincoln Brown - my grandmother

Saturday, May 21, 2016

My Leber Family -- La Prairie, Quebec, Canada

|

Yours truly dressed as a Coureurs de Bois at the Wind River Rendezvous 1987. Even tho I have studied family history since 1972, it wasn't until 2010, that I made a breakthrough and discovered my French-Canadian heritage. See http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2011/10/cowboy-legacy-french-connection.html |

François LeBer -- my 8th great grandfather

François LeBer was born 1626 in France. François LeBer was the child of Robert LeBer and Collette Cavelier

François was an immigrant to Canada, arriving by 1662.

François married (1) Marguerite Leseur before 1655 in France. Marguerite Leseur was born about 1628 in France and died 1662 in Canada.

François and Marguerite had (at least) 1 child:

i Anne Leber was born abt. 1656 in France. Anne Leber was the child of François LeBer and Marguerite Leseur. Anne was an immigrant, arriving by 1672. She married (1) Antoine Barrois 12 January 1672 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal) . Antoine Barrois was born abt. 1647 in France. He died bef. 1689 in Albany, New York, USA. She married (2) Jean Baptiste Lotman dit Albrin 1689 in New York, USA . Jean Baptiste Lotman dit Albrin was born 1662 in New York, USA . He died 30 March 1717 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal).

François married (2) Jeanne Testard 2 December 1662 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal) . Jeanne Testard was born abt. 1641 in Rouen, France. Jeanne Testard was the child of Jean Testard and Anne Godefroy. Jeanne was a Fille à Marier, arriving in New France by 1662. Jeanne Testard was born abt. 1641 in Rouen, France . She died 18 January 1723 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis) .

The couple had (at least) 6 children.

i Joachim-Jacques LeBer (b.10 June 1664, Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal) d. bef. 19 November 1696, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). He married Jeanne Cusson 28 January 1692 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis) . Jeanne Cusson was born 1663 in Trois-Rivières, Québec, Canada (Trois Rivieres) (Three Rivers) . She died 19 March 1738 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis) . She was the daughter of Jean Cusson and Marie Foubert. Joachim-Jacques LeBer died bef. 19 November 1696 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis).

+ii Marie LeBer (b.6 December 1666, Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal) d. 23 December 1756, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). She married (1) Charles Robert dit Deslauriers 9 January 1681 in Contrecœur, Québec, Canada (Ste-Trinité-de-Contrecoeur) . The couple had (at least) 1 child. Charles Robert dit Deslauriers was born 1645 in France. He died bef. July 1684 in Québec (Quebec) Province, Canada (New France) . She married (2) François Bourassa 4 July 1684 in Contrecœur, Québec, Canada (Ste-Trinité-de-Contrecoeur). The couple had (at least) 6 children. François Bourassa was born abt. 1659 in Poitiers, France. He died 9 May 1708 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal) . She married (3) Pierre Herve 22 April 1714 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis) . Pierre Herve was born abt. 1673 in France. He died 5 April 1736 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). Marie LeBer died 23 December 1756 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis).

iii Jeanne LeBer (b.1670, Québec (Quebec) Province, Canada (New France) d. 10 December 1687, Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal). She married Jean Tessier dit Lavigne 21 November 1686 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). Jean Tessier dit Lavigne was born 14 June 1663 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal). He died 6 December 1734 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal). He was the son of Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne and Marie Archambault. Jeanne LeBer died 10 December 1687 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal).

iv Jacques LeBer (b.20 July 1672, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis) d. 21 July 1672, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). Jacques LeBer died 21 July 1672 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis).

v François LeBer (b.11 October 1673, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis) d. 24 April 1753, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). He married Marie-Anne Magnan dite Lespérance 29 October 1698 in Montréal, Québec, Canada (Notre-Dame-de-Montreal). The couple had (at least) 5 children. Marie-Anne Magnan dite Lespérance was born 30 November 1677 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). She died 11 November 1760 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). She was the daughter of Jean Magnan dit Lespérance and Marie Moitié. François LeBer died 24 April 1753 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis).

vi Claude LeBer (b.14 September 1675, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis) d. 10 October 1675, La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis). Claude LeBer died 10 October 1675 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis).

François LeBer died 19 May 1694 in La Prairie, Québec, Canada (St-Philippe-de-la-Prairie) (St-Jean-François-Régis).

Coureurs-des-bois

Francois Leber and his three sons were "coureurs-des-bois"

The most active and most picturesque figure in the fur-trading system of New France was the "coureur-de-bois". Without him the trade could neither have been begun nor continued successfully. Usually a man of good birth, with some military training, and a good education, he was a rover of the forest by choice and not as an outcast from civilization.

Young men came from France to serve as officers with the colonial garrison, to hold minor civil posts, to become seigneurial landholders, or merely to seek adventure. Very few came out with the fixed intention of engaging in the forest trade; but hundreds fell victims to its magnetism after they had arrived in New France.

The young officer who grew tired of garrison duty, the young seigneur who found yeomanry tedious, the young habitant who disliked the daily toil of the farm--young men of all social ranks, in fact, succumbed to this lure of the wilderness.

"I cannot tell you," wrote one governor, "how attractive this life is to all our youth. It consists in doing nothing, caring nothing, following every inclination, and getting out of the way of all restraint." In any case the ranks of the "coureur-de-bois" and "voyageurs" included those who had the best and most virile blood in the colony.

The story of Joachim Leber (1664-1695) -- My 8th Grand Uncle

The following is a excerpt from Narratives and identities in the Saint Lawrence Valley : 1667-1720, by Linda Breuer Gray, Ph. D., McGill University (published between 1999 and 2001 in English and available for download from the Library and Archives Canada at http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk1/tape9/PQDD_0023/NQ50177.pdf)

If identity is expressed largely through language, then language becomes

particularly important for individuals carving an identity in cross-cultural settings.

To be sure, these individuals spoke different languages: Dutch, Iroquois, French,

Abenaki. But within these corporate languages were subsets of language, which

were sometimes called jargon or lingua franca, which allowed communication

across standard language and cultural barriers. To explore the relationship

between language, narrative and identity we can turn to the choices of Anne

Leber's brother, Joachim Leber, who moved as a child with his parents from

Montréal to La Prairie.

Young men, particularly when they are in the middle of an illegal activity,

are difficult to track. It is certain that some young men left these communities

and never returned. Such, apparently, was the case with a man named Jacques

Guitaut. Guitaut received a concession at La Prairie. He had apparently, a

daughter but no living wife. He left the daughter with nuns, probably the

Congrégation Notre Dame. He rnay have planned to pay for his land with furs.

In any case. he departed in 1674 but had not returned by 1678. At this date he

was presumed dead.

The voyages and (perhaps undocumented) returns of Guitaut signal the

pattern which was to engage several men, and occasionally, families, at La

Prairie for the next 175 years. This pattern is absence, due to engagement --

either legal or illegal -- in trade with Indians, Dutch and English. One can gather

from the record that those left on the banks of the St. Lawrence awaited the

return of these traders, often for years. For most of those who did not return, it

is difficult if not impossible to trace their route. They could have, in fact, traveled

up the Ottawa, or to Lake Superior, or only as far as a few miles upstream.

There were probably some who arrived in other communities in the colony (either

lndian or French) and never returned to La Prairie. Some may have arrived in

Indian, English or Dutch communities to the south and stayed there. marrying,

changing their names and religion. Others may have taken a boat to another

part of the colony, to another colony or back to Europe. These who did not

return, however, would not have significantly affected the flow of information to

La Prairie. Quite simply. the narrative of their lives would not have been well-known.

Their absence would be noted, of course, and perhaps was a cause of

mystery or fear to the remaining residents of La Prairie who contemplated similar

voyages. But they did not return to tell their tale. and as such were not an active

part of the evolving community of La Prairie.

There were some who did return, and who, by doing so, drew the attention

of officials in Montréal. In 1681 Frontenac wrote to the King describing "certain

individuals, who resort among the Indians . . .[convey] Beaver to Fort Orange by a

place called Chambly." Frontenac notes that the 'Loups (Mahicans) and Iroquois

of the five nations . . . have pursued trade to Fort Orange for a long time by means of

those of their tribe who have settled at Sault St. Louis,"near Montreal," which is,

as it were, their entrepot for this traffic. He informed the king that he sent guards

to Chambly to keep the French from imitating the Indian trade to Fort Orange.

Other young men from La Prairie returned each year, or even more often.

These include members of some of the oldest families in La Prairie, such as the

Leber, Roy, and Deniau families. Often, in these families, one or more

members worked in alternation or together as a team in the fur trade. One

example of this frequent trading activity by a young unmarried man is Joachim

Leber. Joachim is of particular interest because he, probably against his will, left

for historians a narrative record.

Joachim Leber was born early in 1664. He was baptized on June 10,

1664 at Notre-Dame-de-Montréal as Joachim-Jacques Leber. He was the

eldest son of François Leber and Jeanne Testard. By 1672, as a young boy of

about eight, he had moved with his parents and older step-sister, Anne, to La

Prairie. Joachim worshipped with the Indians of the mission at La Prairie until

1676 when the native mission moved the first time, to the place called

Kahnawake, at the mouth of the Portage River. He may have had an opportunity

to learn native languages at the mission during the 1670s. Too young to be a

soldier for Prouville de Tracy during the raid of Iroquois villages in 1666, he would have been privy to the tales told by the soldiers who returned from this mission and settled at La Prairie. He also would have heard the stories told by returning coureurs de bois in his youth. It is difficult to ascertain exactly what Joachim knew about the route, the Iroquois, the Dutch or the fur trade, but it is clear that unless he was deaf (and later events demonstrate that he was not) he had many opportunities to learn about things which would fascinate a growing boy.

It is possible that Joachim went along on trips to the Iroquois or Ottawa

when he was as young as fifteen or sixteen years old, either as an assistant to

the Jesuits or as a helper for older coureurs de bois. His brother François may

have been a fur trader. The first recorded contract for Joachim's services.

however, was in May, 1685. when Joachim was 21 years old. He was paid the

same wage as a 30-year-old engage, which indicates that the contractor, Claude

Grizonneau (Greysolon), knew that Joachim was experienced. Joachim was

engaged, with others, to go to the Ottawas. Three years later, in 1688, he and

François Bourassa were hired by René Legardeur de Beauvais. Two years later,

in 1690, he was hired with 'Pierre Bourdeau, André Babu, Francois Bourassar again

by Legardeur, this time to go to "Michilimackinac."

Joachim was about twenty-seven years old when he contracted to go to

Michilimackinac -- a longer trip which often took more than one year depending on

weather conditions and good, or bad, relationships with the Indians. It seems

that he came home from this trip. Following Leber in the parish records, we find

that in January 1692 at La Prairie he married a widow, Jeanne Cusson. Jeanne

had two children by a previous marriage with Jean Bareau/Brelau. The records

show that Joachim attended a baptism in February, 1696. Joachim died,

perhaps in 1696, perhaps as part of an Indian raid. Jeanne testified that Joachim

had been "burle par les Iroquois." Jeanne had a child during the summer of

1696, perhaps by the man who was to become her third husband in the fall of

1696, and with whom she would have several more children.

The exact details of Joachim's life are difficult to discern. Though the

record of Joachim's life in New France is scanty, a few patterns emerge.

Joachim had all the training necessary to be a valued employee in the fur trade,

by virtue of growing up in La Prairie. He probably understood at least a few

words of Iroquois or Algonquian, and it is very possible that he was bilingual. His

uncle was the wealthy Montréal merchant Jacques Leber, brother of Joachim's

father François. This family connection opened opportunaties for employment for

Joachim -- indeed several members of this extraordinary family are found among

the engages, as well as in leadership positions in their parish.

It is very likely that he was away from La Prairie during the August, 1690

attack, led by Johannes Schuyler, on La Prairie which left 25 dead. He was also

not at La Prairie during the August 1691 attack by Peter Schuyler and some

Mohawks which left fourteen dead. If he was in Iroquois, as plans for these

attacks were developed, he may have heard about them. The time which

elapsed between his recorded engagements is about two to three years leaving

time, depending on how far he went each time, for a short illegal trip in between

engagements.

Like many of his contemporaries, Joachim married when he was a

relatively old fellow, at about the age of twenty-nine. Also, like many of his

contemporaries, he married a woman who had been married before, and who

had children. He seems to have acquired little -- there is no mention of

belongings. He and Jeanne baptized no children, indicating, among other

possibilities, that he was absent from La Prairie for much of the time between

their marriage in January, 1692 and his demise in 1695 or 1696.

Joachim's life, even though short, was affected in important ways by

proximity to Iroquoia. First, he had the opportunity to learn the language and

perhaps the habits of the Indians he lived with as a young boy. The stories he

heard as a boy would have told him more. Second, he traveled several times on

fur trading business, or, as shall be seen, as a captive, far into native territory.

Third, he married the widow of a man who was killed by the Iroquois. Fourth, he

was closely related to several others active in the fur trade, including his brother,

François, who was, in 1693, a prisoner of the Iroquois and most particularly his

uncle, Jacques Leber, who had favored status among the Onondaga. Fifth, he

was, at least according to his wife, captured and killed by the Iroquois.

There is, however, another source on Joachim. It is a source which tells

us much about the other side of his life, away from the notaries, the priests, and

even away from his fellow engagés. Joachim was alone, and perhaps rather

desperate, when he was interrogated by Governor Benjamin Fletcher of New

York, at Albany, on October 4, 1692. Fletcher had been Governor of New York

for only two months when he conducted "The Examination" of Joachim Leber, a

French Man of Canada, and Native of Mont Royal, taken before his Excellency…

at Albany the 4th of October, 1692.

The scene in Albany was one of high alert. It was near the end of the

raucous trading season. The fur trade at Albany had been in serious decline

since 1690 and the Albany merchants complained that they must have access to

more fun from the Great Lakes region. There had been open warfare in the St.

Lawrence region between Sault Indians and League Iroquois since about 1691.

These skirmishes and battles included Europeans on both sides. It is possible

Joachim was taken captive in one of these small raids or in a larger battle. It is

also possible he was on a simple trading trip to Albany when he was taken.

There may have been a secretary or scribe assisting the governor, and whoever

brought Joachim in for interrogation (a jailer or an Indian or a soldier?) may have

been standing to one side. Nearby was a workhouse where impoverished

Iroquois lived and made wampum. Licensed and illegal taverns and bars

conducted a brisk business within earshot. But Joachim, probably a captive, was

in Albany to be interrogated.

Fletcher's report follows:

That he lived at Prairie de la Magdelain. That it is 60 leagues

from Mont Royal to Quebec. That Mr. de Cellier (de Calliere) is

Governor of Mont Royal. That there are 2,200 men carrying

Arms in his Government, soldiers and Inhabitants. That the

Town of Mont Royal is enclosed with stockades. That there are 53 pieces

of Canon, Brass and Iron, eight Companies of Soldiers, unequal in number,

50 men being the most.

That the Fort of Magdelaine contains 23 families, 400 men in

Arms, 2 pieces of Canon, and 5 Patteraroes. There are 200 men

in the Indian Fort called Canawagne. That there are ten Men of

War (ships) arrived at Quebec, from France, laden with Ammunition,

and that he saw the said Ships. That he hath been taken 43 days,and says, that the day before his being taken he being at Mr.

Cellier's house, he saw a Canon arrive there from Mr.

LeCount, sent to Mr. Cellier to demand the Collem of deeds,

which are usually presented at the concluding a Peace, the

which occasioned him to say there was Ambassadors coming

to treat a Peace.

Upon the Objection made, That there could not be So many

People as he says, that the two Frenchmen were sent to

York sometime since, being now at Canada, did inform Mr.

LeCount, that the English had assembled all their Nations, with a

design upon Canada, which obliged Mr. Le Count to raise all

the men he could possible,which was that number he said.

and says, he knows nothing more.

This document provides some information about Joachim Leber continued

activity, information which is missing from the French record. He seems very

knowledgeable, and perhaps he understands English, for there is no indication of

an interpreter nor any fumbling of answers or misunderstanding of questions.

The specifics are remarkably accurate. For instance, Joachim was a native of

Montréal, but was living in La Prairie. Joachim has adopted the language of

warfare (weapons, defensive and offensive capability) in this situation; it is a

language his interrogators expected and understood. Joachim may have had

other options, such as remaining silent, asking for the assistance of his relatives,

in particular his half-sister Anne Barrois Lotman, or inventing another tale for why he had been captured. With the frequency of travel and intelligence-gathering in the Champlain-Richelieu corridor however, false information was easily detected. Most of the extant testimonies indicate that prisoners provided accurate if sometimes sketchy information.

What details can be learned from his testimony? Since Joachim's family

was well-connected it is entirely possible that he visited with and dined at the

home of the Governor of Montréal; his uncle Jacques Leber had a home

adjacent to Callières' home in Montréal.

Had Joachim seen ships in Québec? Ten men of war? Possibly. Did he

go often to Québec? The distance is about 175 miles; Joachim's estimate of the

distance is accurate. No road yet linked the two cities, but the habitants and

traders traveled by boat. As a young engage and sometime coureur de bois

however, Joachim's patterns probably included visits to La Prairie, business

arrangements and obtaining supplies in Montréal, and upriver trips to the Great

Lakes or to Albany. Quebec would be an unprofitable and lengthy detour, and

there is no evidence that he ever was there. A more typical route for this

information would have been word of mouth, which was the fastest.

Communication was frequent between Québec and Montréal, and between

Montréal and La Prairie. His wife was from Cap de la Madeleine, near Trois-

Rivières, half-way between Montréal and Québec. lt is possible that

communication with his wife's family would have informed him with certainty of

"ten Men of War."

Joachim's estimates of the defense capabilities of New France, while not

believed by Fletcher, were fairly accurate. In 1689 the French forces in New

France were consolidated into twenty-nine companies of fifty men each. In 1699

the number of men per Company was reduced from fifty to thirty, probably due to the difficulty commanders experienced in keeping their companies at full

strength; in this the financial strain these forts placed on the colony's finances

was a significant factor? The men defending La Prairie were probably soldiers

billeted there. These soldiers were distributed throughout the St. Lawrence

valley. There were 1,418 regular soldiers in New France in 1688. Soldiers

were also billeted at Sault St.-Louis. The record indicates that Frontenac sent

600 militia, Indians, and regular soldiers to Mohawk territory in 1693, just one

year after Joachim testified in front of Governor Fletcher.

Joachim's narrative moves from the defense of his home town to the

wartime capability of Sault St.-Louis. Like roost of his superiors, he thought of

the mission as a recruiting ground for the defense of New France.

Joachim also has news of a peace. Though not specific, he implies that it

is a peace which will strengthen the defense of New France. Warfare between

League Iroquois (mostly non-Christians) and Sault residents (some of whom

were ardent Christians, others of whom at least tolerated the presence of the

Jesuit priests among them) had been constant since December 1691. By 1692

La Prairie was a garrison town, with soldiers billeted there from other parts of the

colony. The attacks and counterattacks were reaching intolerable levels.

Individuals sometimes refused to fight if they did not know the exact targets.

It was not uncommon for individual soldiers, particularly native soldiers, to ask the

names of individuals in the opposing party before commencing to fight. A

peace with the Iroquois was in fact imminent, following Canada's devastating

raids on the Iroquois in 1690 and 1691. An Oneida, Tarriha, approached

Frontenac in June, 1693 to propose peace. Frontenac's frenetic pattern of trade,

warfare and tough diplomacy was bearing fruit, and perhaps in his recent travels

Joachim Leber had heard rumblings of this.

In general then, Joachim's story is both accurate and precise. He

appears to have been traveling without a permit, or to have been, as he would

have it, captured near a settlement. It seems likely that he was engaged in some

private illegal trading in upper Iroquoia when he was captured. This possibility is

strengthened by the fact that the governor did not ask Joachim the purpose of his

travel, or why he was traveling without a permit. He may have been a captive of

a native group. It is also possible that he had been or would be tortured and

tested for adoption by the native group that captured him. He may have

returned to La Prairie and later died at the hands of the Iroquois, although the

exact timing of his travels is impossible, at this distance, to trace.

Joachim Leber is an example of a young man raised at La Prairie whose

life, at least as much of it as we can reconstruct, was centered around the fur

trade. There is no evidence of significant agricultural activity on his part. He did

not help support his mother, though other neighbors and a younger brother did.

He did not receive a concession, and can be documented in lroquoia or New

York in 1685-1690 and 1692. As a part of the fur trade he traveled to Montréal,

to the Ottawas, to Michilimakinac, and, perhaps under force, but likely more than

once willingly as well, to Albany. Yet, if we believe the testimony of his wife, who had two husbands meet similar ends, this proximity to the natives did not save him from a violent death at the hands of "les Irokois."

He had no children, and perhaps knew of his wife's liason with the man

who was to become her third husband. Joachim's burial was not recorded in

New France. It is entirely possible that he remained in Iroquoia, traveled further

into the pays d'en haut, or changed his identity and traveled to another colony. It

is not possible to know for certain how or when he ended his days.

For scholars of Canadian history, Joachim's life is more familiar than

Anne's. Joachim is a resident of New France whose journeys are related to the

fur trade. His testimony is a rare narrative source from an individual in a

population where narrative sources are almost non-existent. This was the story

he told, probably under duress, to the officials in Albany. What story would he

tell in Michilimackinac? In La Prairie? In Montréal? Surely, it would not be the

story recorded by the Albany court officials. Joachim's narrative, however

truthful, was situational. It was tailored for the -- very uncomfortable -- situation

in which he found himself. As a means of survival, he had learned to use the

language of war and diplomacy in telling his story; this was the language his

interrogators wanted to hear. Arguably, he had little choice about what to Say in

this context. It is reasonable to assume that any fairly competent young man in

his situation would have offered information about battle readiness in New

France. As a source about Joachim's identity, or self, this narrative is not

introspective. However, it provides considerable information about his

knowledge, his language, his affiliations and his understanding of his

environment.

His activity at the time of his capture is critical to interpreting his narrative.

If he was taken captive at or near La Prairie, for instance, while tending a crop,

he could relate his account similarly in Albany and, later, in Montréal upon his

return. If he was trading illegally, providing information to the Albany officials in

return for some other consideration, or engaging in traitorous activity, he could

not have provided the same account in both places. On his return he would

readjust his narrative to his situation. His narrative and perhaps, as a result, his

sense of his place in the world, would shift a bit with each retelling.

In addition to the existence of his narrative, there is another remarkable

"coincidence" about this testimony. What is extraordinary about his involuntary

appearance before the court in New York is the timing. Joachim appeared alone

in the court in the region where his stepsister, Anne, had been living for nine

years. It is worth underscoring that he did not, in his testimony, mention his

family members, and did not ask for assistance from his half-sister or her

husband. In the following year, perhaps while Joachim was still in New York. his

brother François and his uncle Jacques Leber were both in Iroquoia. Jacques, in

fact, had just been given an Iroquois youth in exchange for his son Jean/Jacques

Leber dit La Rose who had died defending La Prairie. Four members of this

family: Anne, Joachim, Jacques and François were in the New York region during

one twelve-month period. At first glance it would appear that some members of

the family might be engaged in activities which endangered the lives of other

members. Their goals and intentions were different, but were their goals related?

It is difficult at this distance to say, but it appears likely, and later events

support the possibility, that these members of the Leber family were assisting

each other in their journeys, trade and settlement in lroquoia and New York.

Knowledge of passable routes, prices of furs, and news about the arrival or

departure of a new governor or Protestant minister were vital to travel, settlement

and trade in this region. This is the kind of knowledge that Anne Leber Barrois,

Joachim Leber, François Leber and Jacques Leber would have gleaned from

their time in lroquoia or New York, and would have been able to pass on to other

family members or trusted associates. It also appears clear that information

about raids, counter-raids and preparations for war could travel easily along this

"information highway." For instance, Anne Leber was in New York in 1690 and

1691 when plans for the attack on her home community were made. Her

stepmother, stepbrothers and stepsisters still lived in La Prairie. Is it likely that

Anne knew of these plans. Did she attempt to warn the residents of La Prairie?

Did anyone else? Did any warnings arrive at La Prairie? It is hard to know for

certain. It does seem clear that members of this family, a family which spanned

and peopled the Albany fur trade route, a family which knew, intimately, both

poles of that route, sorted information and choices constantly. The narratives

that they told about their lives were necessarily complex and malleable -- tailored

for each situation.

This simple story, Joachim Leber, engagé, François Leber, engagé and

prisoner, Anne Leber wife and mother, and Jacques Leber, their uncle, a

merchant, ends where it began, in the village of La Prairie. It also moves from La

Prairie to Albany, to the castle of the Onondagas, and to major affairs of state.

However it describes these events not by following official correspondence, but

rather by following the movement of individuals.

The "fate" of the Leber family in the 1690s begins to look more sculptured,

less arbitrary, in light of the information provided by linking the New York records with the records from the St. Lawrence Valley. Many of the other members of this family lived at La Prairie: Joachim's mother Jeanne Testard, his wife Jeanne Cusson. These residents of La Prairie knew and perhaps spoke of the absence of their family members. It is certain that the members of this family were concerned about the well-being of other family members in the difficult first years of the 1680s and 1690s. The story of this family was taking critical turns during these decades.

Narrative and Identity, Anne, "Anna" and Joachim

The early 1690s were pivotal years for this family, years which required a

shaping of their family story for themselves, for their neighbors and for

government officials. They were pivotal years for the border communities of La

Prairie and Schenectady as well. In addition to the travels of Anne, Joachim and

their uncle Jacques mentioned above, Anne's stepbrother, Joachim's brother

François, was believed to be a captive of the Iroquois in 1693. This is the

decade when the worst attacks took place on La Prairie. With the presence of

Anne, Joachim and Jacques in Albany, and of François in Iroquois, these attacks

take on a new dimension. In addition to the question raised earlier about

whether one part of this family may have warned another about impending

attacks, are other questions. With rumors flying, as they often did in both Albany

and La Prairie, what choices faced Anne? Did she ask the attackers to spare

certain houses? To carry a message? Similarly, if Jeanne Testard knew her son

Joachim and her stepdaughter Anne and her husband were in Albany, what

choices faced her as she heard rumors about attacks on "les Anglais"?

The two examples of Joachim Leber and the family of Anne Leber point

out three other aspects of the effect of contact between French residents of La

Prairie and the English or Dutch: the importance of family networks, the

importance of oral communication, and the lack of written records about such

contact in New France.

First, they were in the same family. Certain families appear to have had

more contact with New York and New England than others, and the extended

Leber family appears to be one that had much contact with New York fur trading

networks.

Second, neither Anne nor her step-mother could read or write. During the

seventeenth century La Prairie did not have a schoolmaster or a teacher, so it is

unlikely that Joachim could read or write, either. Therefore it was either through

written messages composed by someone who wrote, or through trips like that of

Joachim, or others from La Prairie, that Anne heard of the death of her father, or

that her mother, Jeanne, was informed of the remarriage of Anne to a man

named "Elbrain." The dearth of surviving written material in the Albany records

signals that it was largely oral information, stories, which this family sorted

constantly in their decisions about travel and protection.

Third, it appears that the interlude that the Barrois family spent in New

York went almost completely unrecorded in the French records. Jeanne

Testard's "inventaire des bins," memos about Barrois' escape, a complaint from

Claude Caron about tasks he had to perform in François Leber's absence, and a

note in the baptismal records of La Prairie de la Magdalene are the only signs of

the sixteen-year absence of an entire family.

A final and not inconsequential note about the movements of the Leber

family during the years from 1683-99: one of Jacques Leber's sons fought as a

solder at the 1691 battle of La Fourche defending La Prairie -- Jean/Jacques

Leber dit La Rose died there? In 1693 Jacques Leber travelled as part of the

military campaign of 300 Canadians, 100 soldiers and 230 Indians that attacked

the Mohawks in their own territory against the Iroquois. He wrote an account

of this campaign which he sent to France with his son. Dùring this campaign

Jacques Leber went to Lac Saint-Sacrement (Lake George). Jacques' account

relates that an lndian gave him one of his own sons in exchange for Jacques'

son (probably Jean/Jacques dit La Rose). Jacques' native "son" apparently

could not keep up with the group -- he was, according to Leber, laden down with

things given him, possibly by women. Because he lagged behind he was killed,

but Leber's report is unclear about the identity of the adoptive boy's killer. He

could have been killed by English or Indians.

Jacques Leber's account is, in part, an apology for this death of one

charged to his care, a death which could have had serious repercussions.

However the fact that the natives remembered, three years following the death of

his son in battle, to repay a debt to him by giving him an adoptive son, indicates a

strong and lasting relationship between Jacques Leber and the Onondagas.

In 1694, Jacques Leber's kinship with the lroquois was described by

Teganissorens at a council between lroquois and Frontenac. During the

discussions, Teganissorens, an Onondaga diplomat and leader, announced,

and confirmed with a wampum belt, that the lroquois had adopted Sieurs de

Longueil [Longueuil] and de Maricourt in the place of Monsieur Le Moyne, their

father, as our children, and Monsieur Leber as our brother... They will have nothing

to fear whenever they visit us, and will be received when sent by you. Jacques

Leber was honored on both sides of the Atlantic; he was ennobled in 1696 by

Louis XIV. In 1706, following the death of Jacques Leber, the Onondagas paid

homage to him as was customary to do for French heads of state.

The purpose for this long digression is to pose a question. Of what

significance is it, if any, that Jacques Leber, Anne Leber, François Leber and

possibly Joachim Leber, who, after all, was interrogated in October, 1692, and

perhaps had to spend the winter in Albany or Iroquoia, were all within a few miles of each other in 1693, with the most powerful of the three, Jacques, apparently endangering the others' lives. Jacques apparently, also, at this time in his life and others, cemented relationships with Iroquois, probably Onondaga, who could affect or even threaten the lives and fortunes of those who lived in Albany, or indeed in La Prairie.

They may have been responding to changes in the fur trade market. As

has been observed, the Albany fur trade collapsed in the years 1689-1692. The

Commander in Chief Governor Henry Sloughter, who arrived in the colony in

March 1691, found, in August, 1692, the Indians weary of War and all the

outsettlements forsaken... [I found Indians] very difficult and much inclined to a

peace; however with great industry I have reclaimed them in New York's service,

as allies. In September, 1692, his replacement, Benjamin Fletcher, found "decay

of trade" and "poverty of the people" at Albany. By March, 1694, the Dutch

observed, the "Indians are staggering."

The presence of at least three and possibly four members of the Leber

family in Albany in 1693 could be due to several factors. The most likely possible

explanation is that the Leber family was attempting to increase their profit margin

in a collapsing fur market by selling more fun in Albany and returning to New

France with more currency and more imported goods to sell. It is also possible

that Jacques planned to take advantage of his participation in the military

campaign in order to attempt to rescue or ransom Joachim or François, or to find

Anne Leber.

The presence of many members of the extended Leber family in Iroquoia

in 1693 adds another layer of interpretation, for their stories were brought home

not only to La Prairie and Montréal, but were told also in Albany and at the

council fire in Onondaga. As signaled by the example of Joachim Leber, the

language used to describe one's purpose was necessarily tempered and adapted

by the stories told and by the settings in which they were told. The language

Joachim used to mediate his identity in the dangerous border region was the

language of warfare.

|

| Is it in the DNA? Jerry England (left) and friends at Hart Canyon Rendezvous 1987. When this photo was taken I had no idea I am descended from the Father of the Fur Trade. |

My Lineage from Joachim Leber:

Joachim Leber (1664 - 1695) - 8th great-uncle

Francois Leber (1626 - 1694) - father of Joachim Leber

Marie Le Ber (1666 - 1756) - daughter of Francois Leber

Marie Elisabeth Bourassa (1695 - 1766) - daughter of Marie Le Ber

Joseph Pinsonneau (Pinsono) (1733 - 1779) - son of Marie Elisabeth Bourassa

Gabriel Pinsonneau (Pinsono) (1770 - 1813) - son of Joseph Pinsonneau (Pinsono)

Gabriel (Gilbert) Passino (Passinault) (Pinsonneau) (1803 - 1877) - son of Gabriel Pinsonneau (Pinsono)

Lucy Passino (1836 - 1917) - daughter of Gabriel (Gilbert) Passino (Passinault) (Pinsonneau)

Abraham Lincoln Brown (1864 - 1948) - son of Lucy Passino

Lydia Corinna Brown (1891 - 1971) - daughter of Abraham Lincoln Brown - my grandmother.

Sunday, May 15, 2016

Back Trails and Tales of a Western Family

Mom's Family...

My Leber Family -- La Prairie, Quebec, Canada

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2016/05/my-leber-family-la-prairie-quebec-canada.html

Cowboy Legacy -- Discovering Family Roots

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2013/10/cowboy-legacy-discovering-family-roots.html

Cowboy Legacy -- A Million Ancestors in 20 Generations

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2013/08/cowboy-legacy-million-ancestors-in-20.html

Cowboy Legacy -- Pistol Packin' Momma

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2012/12/cowboy-legacy-pistol-packin-momma.html

Our Quaker heritage began with John Hallowell (1648-1706)

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2016/04/our-quaker-heritage-john-hallowell-1648.html

Great Granddad Minted America's First Coins

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/08/great-granddad-minted-americas-first.html

Great-Uncle Rene Was A Coureurs Des Bois

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/08/great-uncle-rene-was-coureurs-des-bois.html

Great Granddad Was Murdered By Iroquois Indians

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/08/great-granddad-was-murdered-by-iroquois.html

Great Grandma Was A French King's Daughter

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/08/great-grandma-was-french-kings-daughter.html

Great Granddad Was a Threshing Machine Builder

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/07/great-granddad-was-threshing-machine.html

Great Granddad Was The Village Blacksmith

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/07/great-granddad-was-village-blacksmith.html

1908, Montana Schoolmarm Finds Romance

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/05/1908-montana-schoolmarm-finds-romance.html

Thank Goodness For Traveling Photographers

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/05/thank-goodness-for-traveling_87.html

Great Granddad at the Battle of New Orleans

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2015/03/great-granddad-at-battle-of-new-orleans.html

Great Grandfather Died During the Civil War

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2014/05/great-grandfather-died-during-civil-war.html

Great Granddad Died at Sea in 1847

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2014/05/great-granddad-died-at-sea-in-1847.html

Great Granddad was a Cheesehead

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2014/01/great-granddad-was-cheesehead.html

Was Cousin Daniel A Potawatomi Chief?

http://a-drifting-cowboy.blogspot.com/2013/10/was-cousin-daniel-potawatomi-chief.html

Great Granddad was a French Sharpshooter